Another Wildfire.

My wife and I bought a home in Pacific Palisades. It was located at the back of the last canyon before the beach. There was only one way into the canyon. The house was new and lovely. I had to drive more than an hour to get to the University of Southern California and my office in the College of Business. Living in the Palisades was worth the drive.

I was sitting in my office preparing for an MBA finance class. It started in less than 30 minutes. Meetings had occupied my day, so I had not paid attention to the news. The phone rang. My wife said I had to come home immediately. I thought she was kidding.

She knew my work schedule. I assumed she had forgotten my MBA class was about to start. She had not forgotten. She said, with grave concern, that a wildfire was coming over the hills into our canyon, and the fire would destroy our home. Authorities told her that we had approximately two hours until the fire reached our home. “You must come home and help me pack the cars,” she stated forcefully.

Immediately, I jumped up and ran to my car. After driving well over the speed limit for less than an hour, I reached the entrance to the canyon. The police told me I could not enter the canyon. We had a brief but impactful conversation, and the officers said I could go in to get my family.

My wife had a lot of things on the front porch when I arrived. There were suitcases with clothes and toiletries, some snacks, several boxes of pictures, and a few family mementos. She had done an incredible job of making sure we took the critical items with us.

We quickly loaded our cars. In less than five minutes, I took photos of all the furniture in the house so that we would have a basis for our insurance claim. Then, with our son and daughter in tow, we drove away. The fire was only three blocks away. A helicopter was dropping water on our house and the other four homes on our side of the street. It never occurred to us that we would see our home again. I know the panic that people feel when a wildfire is racing toward them; I can relate to the helpless feeling of seeing your home about to go up in flames.

The Home Burned Down.

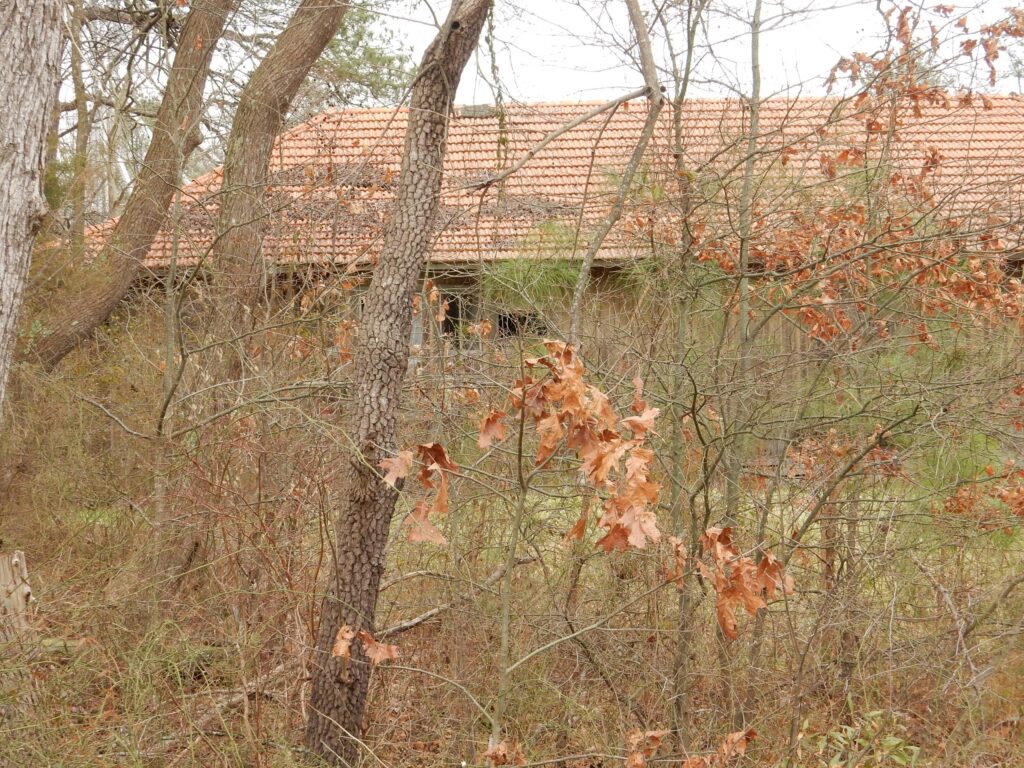

However, the house did not burn down. By some miracle, some would say the laws of physics of combustion, the fire did not destroy our home in 1978. It did burn down last week. (I am not sure, but I believe that the 1978 fire was started by some driver throwing a cigarette out of his car window.)

The blame game for the 1978 fire was vociferous. Local authorities were criticized for not getting the fire under control, for undergrowth that had not been cut, etc.

The blame game for the current wildfire has produced claims that the governor cut the fire suppression budget by 100 million dollars, the water ran out, and the mayor was not competent; this is the shortlist. History will determine those who erred. I cannot.

What Questions Need To Be Answered?

Beyond laying blame, key questions will have to be answered in the next five years. Who will pay the losses, who will write insurance in the future, and what has exacerbated insurance coverage problems? These seem like straightforward questions; the first two are not.

Before these questions are answered, it is essential to compare Florida and California. Both constantly face disasters. For Florida, it is hurricanes; for California, it is wildfires and earthquakes. Both states have seen private insurance companies reduce the amount of coverage they will write because insurers are designed to handle standard loss patterns, not disasters. As insurers have reduced the amount of protection they write in both states, policyholders have been forced to get coverage from the state. In California, the last resort market is the FAIR plan. In Florida, it is Citizens Insurance Company.

Who Will Pay The Losses?

Now, the first question is, "Who will pay the losses?" It seems evident that private insurers and state insurers will pay claims in California and Florida when a disaster occurs. There are some problems, however. First, if an insurer loses a significant amount because of a disaster, it will recoup some of the loss from increased insurance premiums in the future. So, all the policyholders in a state end up paying for at least a portion of the catastrophic losses.

If an insurer goes insolvent because it cannot pay disaster claims, its losses are paid by the state guaranty fund. However, if the guaranty fund runs out of money, its losses are paid by insurers and, eventually, policyholders through higher rates.

It gets more complicated. If the state insurance carrier, FAIR in California and Citizens in Florida, runs out of money, insurers have to cover the losses. (In Florida, the insurers add a fee to every policyholder's policy to cover Citizens' losses.) The whole process is clouded by the fact that the private insurers and the state funds have reinsurance. For those who are not familiar with insurance terminology, an insurance company can write coverage for a home. It then buys insurance (reinsurance) from another company to reduce its exposure on that home. For example, it might provide $200,000 in coverage on a house but lay off half of the exposure with a reinsurer, so it only loses $100,000 net in the event of a total loss. The most well-known reinsurer operation is Lloyd's of London.

This seems complex. So, let's simplify it. The whole insurance process is subject to a domino effect. A significant catastrophe could wipe out a large portion of Florida's or California's insurance system capital, public and private.

Who Will Write Coverage?

The answer to the second question, "Who will write coverage?" also is not simple. California will continue to see private insurers leave the state or reduce the coverage they are willing to write, no matter how much the state tries to make insurers stay. (This will also happen after the next significant Florida hurricane.) The FAIR plan in California will see tremendous growth in the number of policies it writes since it is the market of last resort. This means that if another catastrophe occurs and the FAIR plan does not have adequate reserves, the insurers who have not left California will have to cover the losses.

While I am opposed to federal programs, the only way to stabilize the insurance market in states like California and Florida is for the federal government to provide federal reinsurance. Of course, this would then make everyone in the United States responsible for losses in California and Florida.

What Has Exacerbated Insurance Coverage Problems?

The most important question is, "What has exacerbated insurance coverage problems?" This question is simple; the answer also is simple. "I did." Let me explain.

And, hurricanes pounded Florida long before the turn of the twentieth century.

So, how did I create the problem? First, I elected to buy a home in the Palisades. It was surrounded by brush, subject to dry spells, and often buffeted by Santa Ana Winds. It was only a matter of time before the house was destroyed by fire. Fortunately for me, it did not happen in 1978.

The fires in California prior to 1850 did not matter because there were few homes or commercial buildings. The growth in California has put large segments of the population in danger and the insurance industry in a precarious position. It is not the number of acres burned that makes the recent wildfire significant; it is the loss of life and property. (For an interesting overview of recent California wildfires, click here.)

After living in California, I moved to Florida near the coast. Where I live has been pounded on a regular basis by hurricanes. I do not have to live near the coast; I want to. Simply put, people like me have created the problem by choosing to live in areas prone to disasters. I worked on a project in Alabama where the homes were built on a barrier island. I told the state they should not insure the homes. The state did. Several years later, the island was wiped clean. I am sure someone will eventually build homes on the barrier island.

If people want to live in locations like California and Florida, they will have to be willing to pay a price for their selection. However, at some point, the costs will become so high that they will work to get federal relief, or they will move. The latter can cause financial disruption. In some areas of the west coast of Florida, after the last hurricane, property values plummeted as people looked to move to safer locations. The supply of homes went up; the demand for homes went down. That said, I am not leaving Florida; I will pay the higher premiums. Until people choose different living patterns, insurance problems will only get worse for California and Florida.

PS: A few months after our house was almost destroyed by fire in California, my wife and I experienced an earthquake. We immediately decided to leave Pacific Palisades and move to the East Coast, where we would be safe--we thought.